improving standards alone does not guarantee

safer construction. There are some important

differences between building housing in developed

and developing countries which would have to

be considered when deciding how to make post-

disaster reconstruction safer. These differences are

summarised on page 3.

When there is a lack of capacity in a developing

country to devise standards in specialist areas,

such as disaster resistant structures, it becomes

tempting to adopt the standards of developed

countries that have proven to withstand disasters.

Thus, several Latin American countries have

adopted standards for earthquake resistance

from the USA, and Asian countries have derived

standards from Japan or New Zealand. This often

only had a limited positive impact, because:

• The standards are set at a very high level which

makes them unaffordable to a majority in

developing countries.

• The standards over-emphasize engineering

solutions, encouraging the use of modern

materials and techniques by building

contractors, rather than allowing for informal

construction. They overlook vernacular

construction and its own disaster-resistant

elements.

• The capacity for adequate implementation and

inspection is often lacking.

The adoption of such ‘ideal’ standards may

have worked for some buildings, but generally has

helped make low-income housing less vulnerable to

disasters. That is not to say that having standards

is wrong, just that they need to be fit for purpose.

Having the best standards may only protect a small

proportion of the population. Instead, moderate

standards with simple processes of compliance

might be able to protect a majority from all but the

highest magnitude disasters.

Finally, some consideration needs to be given to

retro-fitting as an option for strengthening existing

dwellings, some of which may have suffered

repairable damage. Rather than replacing such

dwellings with entirely new ones of a high standard,

retro-fitting is a much more cost-efficient solution

for providing disaster resistance. Standards for

reconstruction should therefore not just cover new

buildings, but also the retro-fitting of existing ones.

A People-Centred view of standards

Historically, building regulations, codes and

standards were developed to ensure protection of

people from illness, injury and accidental death

when they live, work-in or visit a building. However,

this system of building control developed largely

for the public good has often failed to deliver

an adequate level of protection against natural

disasters in developing countries. Past experience

shows that regulatory frameworks derived from

developed countries are often inappropriate for

developing countries (see e.g. Yahya et al., 2001).

Reform of regulations can take several decades

because of the need to pay attention also to the

processes of applying, decision making, appealing,

communicating with applicants, record keeping and

dealing with non-compliance. If those processes

are too complex and costly, few property owners will

bother to comply (see e.g. de Soto, 1989: chapter

2). It is important for reform to have a group of

champions who manage to overcome the obstacles

thrown in their way by stakeholders who have

something to gain from maintaining the status quo.

In People-Centred Reconstruction, people are

what matters most. In other Tools and a Position

Paper on PCR, we have argued that the ultimate

aim of PCR is more than just achieving safer

housing; it is to make the people themselves more

resilient. In the reconstruction process itself, this

means empowering them by involving them much

more in decision making. The process should not

just aim to rebuild houses, but also livelihoods,

local markets and social networks, as these all are

crucial in generating resilience.

If people are what matters most, then standards

should protect people first and foremost, and aim to

substantially reduce the number of casualties that

natural disasters cause. Lives cannot be replaced,

but buildings and other assets can, and often

are with the aid that is given following disasters.

Applying this principle to building practice, means

that a certain amount of damage to buildings could

be acceptable, but their collapse on people inside

should be prevented.

This thought can be translated into regulations

and standards to define the weight and integrity

of roofs and intermediate floors, the strength and

technologies for supporting structures, and their

connections. However, if for example walls have

no structural contribution, they could be allowed

to be relatively flimsy. For certain types of high-

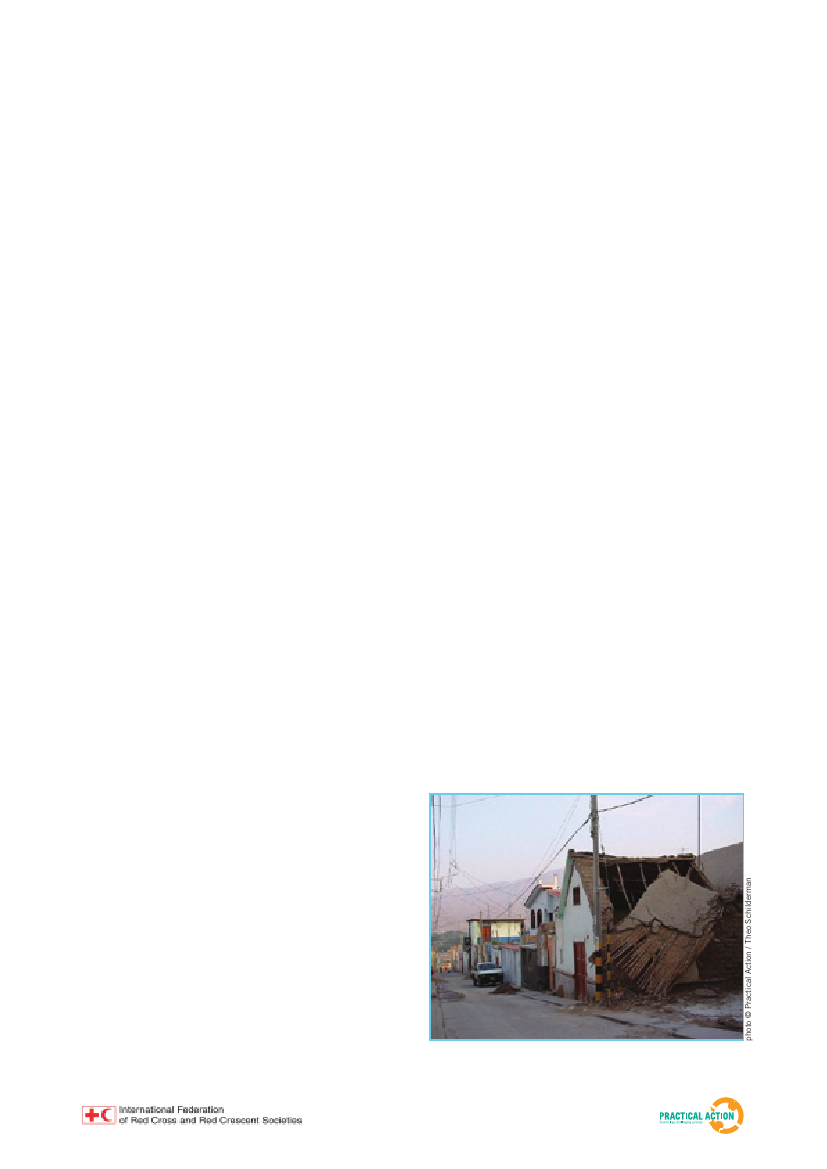

The inhabitants of this house in Moquegua, Peru had a narrow

escape, because the failing roof slid sideways rather than falling

in on them.

4